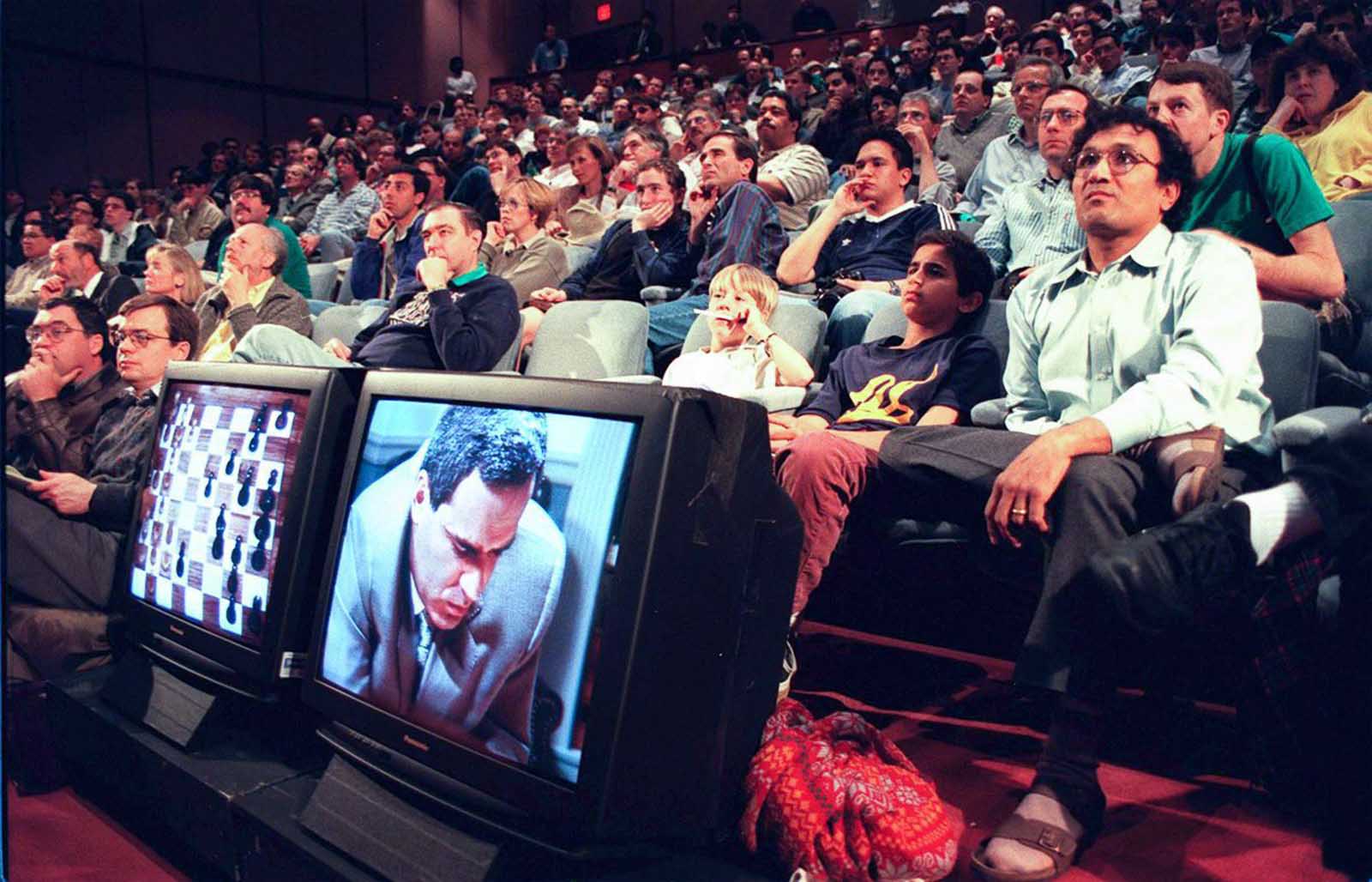

Spectators watch a broadcast of the final, decisive game in the rematch between Garry Kasparov and the IBM computer Deep Blue. May 11, 1997.

It’s 1997, and Garry Kasparov is hunched over a chessboard, visibly frustrated. He’s fidgeting in between turns and shaking his head in disbelief as he waits for his opponent to put the final touches on an inevitable victory.

Finally, Kasparov makes his move, stands up, and races away from the board. He raises his arms, astounded that he was beaten by a machine.

His opponent was the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue, a machine that was capable of imagining an average of 200,000,000 positions per second. But going into the match, Kasparov was confident.

He was the Michael Jordan of chess at the time. He had been beating chess-playing computers since the ‘80s (he’ll remind you that he defeated an earlier version of Deep Blue in 1996) and was considered nearly unbeatable.

So when Kasparov, one of the greatest chess players of all time, lost to a computer in front of a global audience, people began to wonder whether it was just a matter of time before machines surpassed humans in other aspects of life.

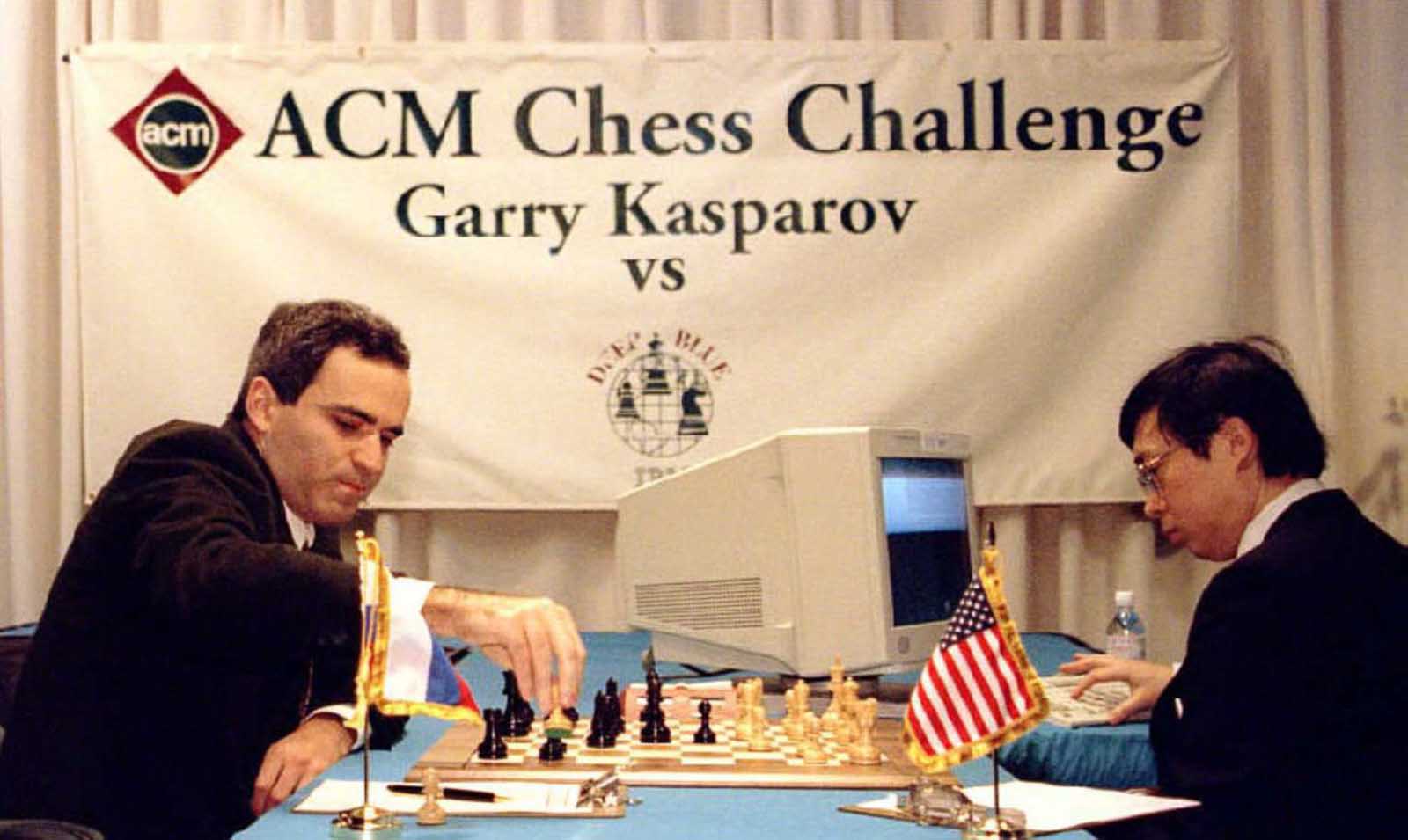

Garry Kasparov takes a pawn in the opening moves of a six-game match against Deep Blue, operated by designer Feng-hsiung Hsu. February 10, 1996.

Immediately after the match, Kasparov was bitter. In December 2016, discussing the match in a podcast with neuroscientist Sam Harris, Kasparov advised of a change of heart in his views of this match.

Stated Kasparov: “While writing the book I did a lot of research – analyzing the games with modern computers, also soul-searching – and I changed my conclusions. I am not writing any love letters to IBM, but my respect for the Deep Blue team went up, and my opinion of my own play, and Deep Blue’s play, went down. Today you can buy a chess engine for your laptop that will beat Deep Blue quite easily”.

This particular game was the first in a match of six held in Philadelphia. Kasparov rebounded in the following five games, fighting the computer to two draws and three victories, winning the overall match.

Deep Blue’s win was seen as very symbolically significant, a sign that artificial intelligence was catching up to human intelligence, and could defeat one of humanity’s great intellectual champions.

Later analysis tended to play down Kasparov’s loss as a result of uncharacteristically bad play on Kasparov’s part, and play down the intellectual value of chess as a game that can be defeated by brute force.

Deep Blue at IBM headquarters in Armonk, New York.

A view of Deep Blue’s display screen.

A computer programmer at IBM headquarters in Armonk, New York.

Deep Blue developer Dr. Chung-Jen Tan applauds Garry Kasparov after his victory over the supercomputer in the six-game match.

Kasparov poses for a photo while training for his rematch against Deep Blue.

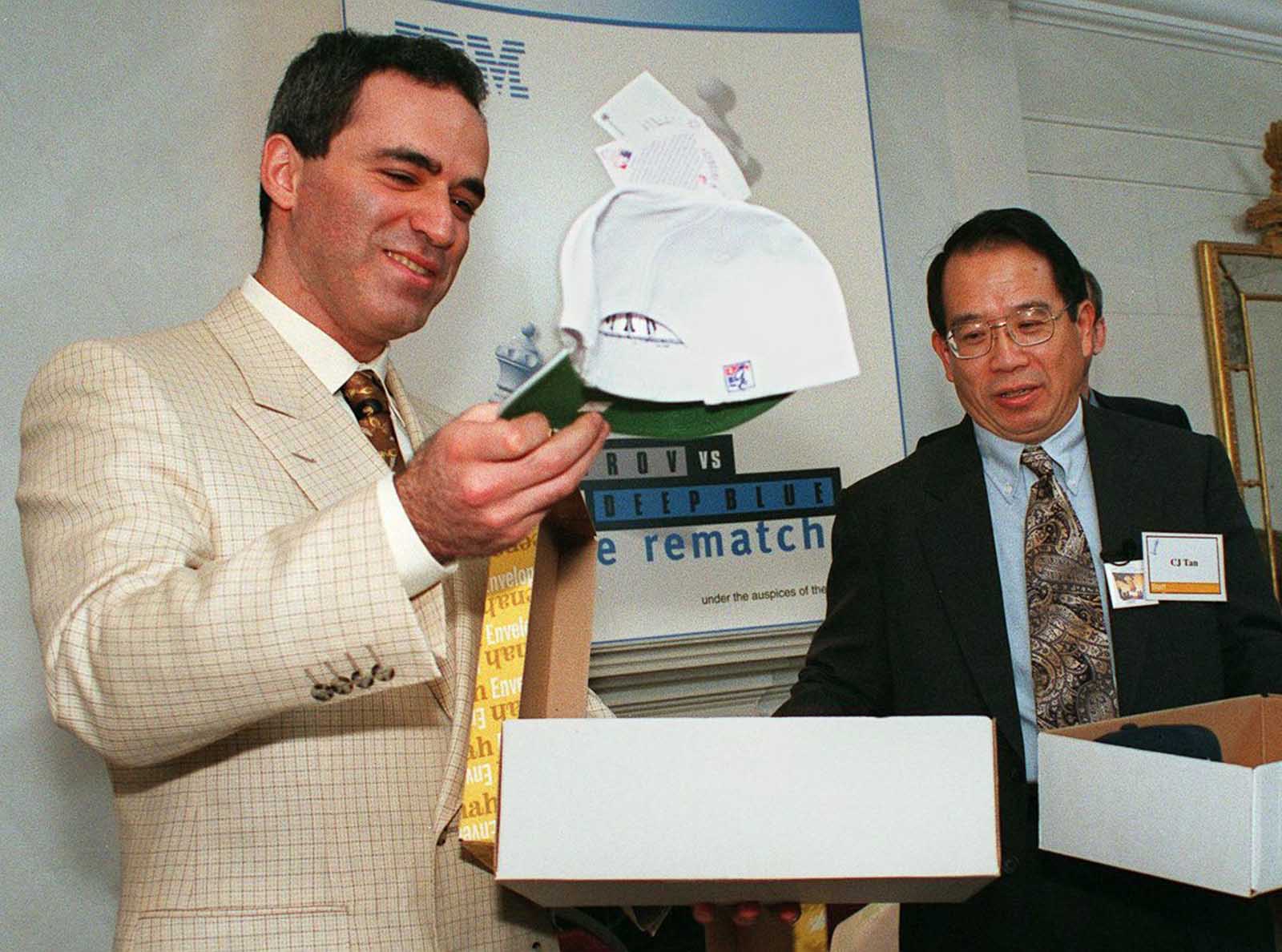

Kasparov lifts a white hat which signifies that he will have the first move in his rematch with Deep Blue.

Feng-hsiung Hsu prepares Deep Blue before Kasparov makes his opening move in the first of six games.

Kasparov contemplates his opening move in Game 1 of the rematch.

Kasparov moves his first piece, a knight, in the first game of the rematch.

Spectators watch the first game. March 3, 1997.

IBM scientist Murray Campbell makes a move for Deep Blue in Game 2.

Kasparov makes a move in Game 2.

Kasparov ponders a move in Game 3, after winning the first game and losing the second.

Spectators watch a live broadcast of Game 3.

The IBM Deep Blue team pose for a photo after Game 4 ended in a draw, leaving the score still tied.

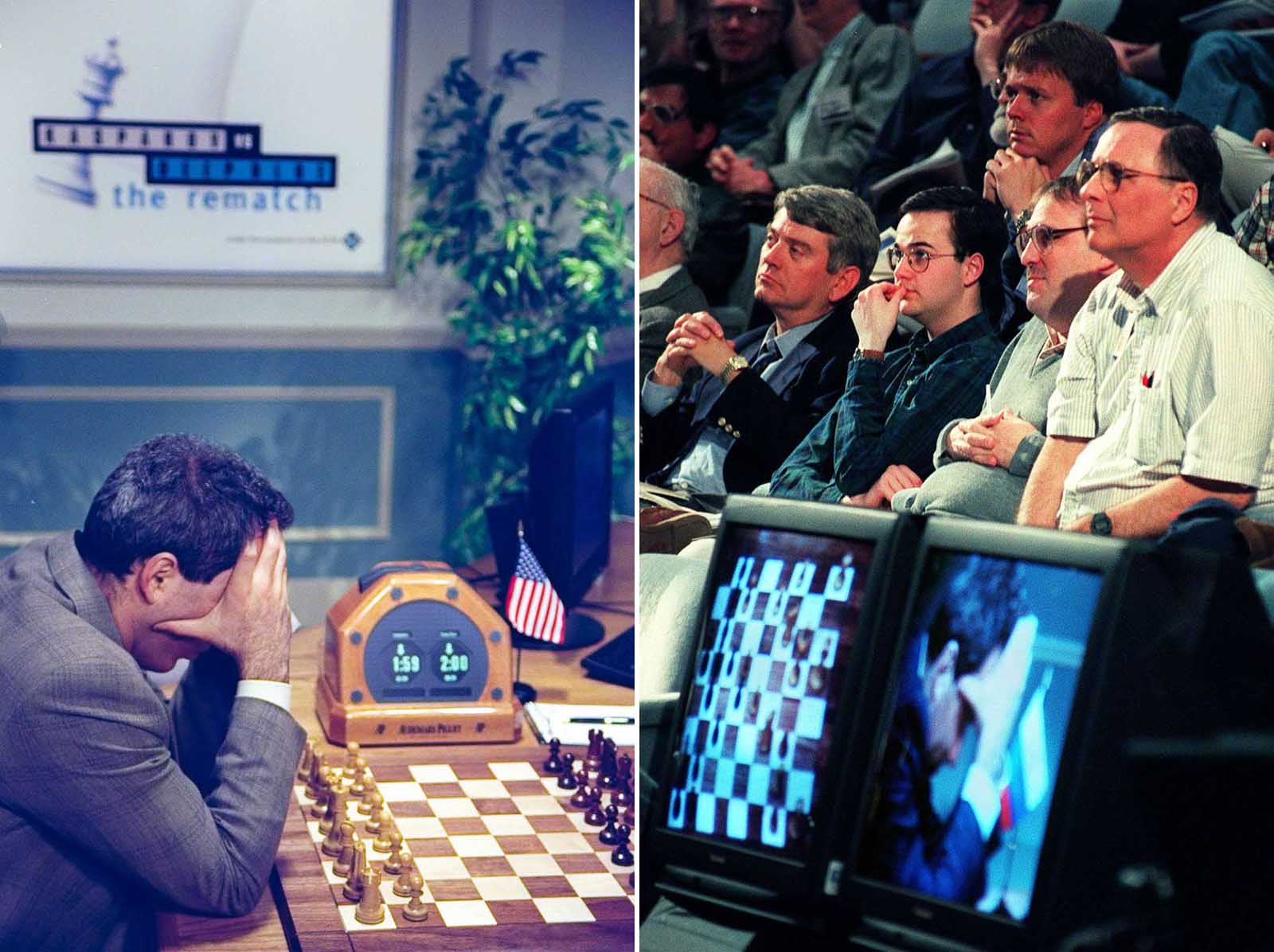

Kasparov struggling against Deep Blue.

The anticipation.

Kasparov considers his next move early in Game 5.

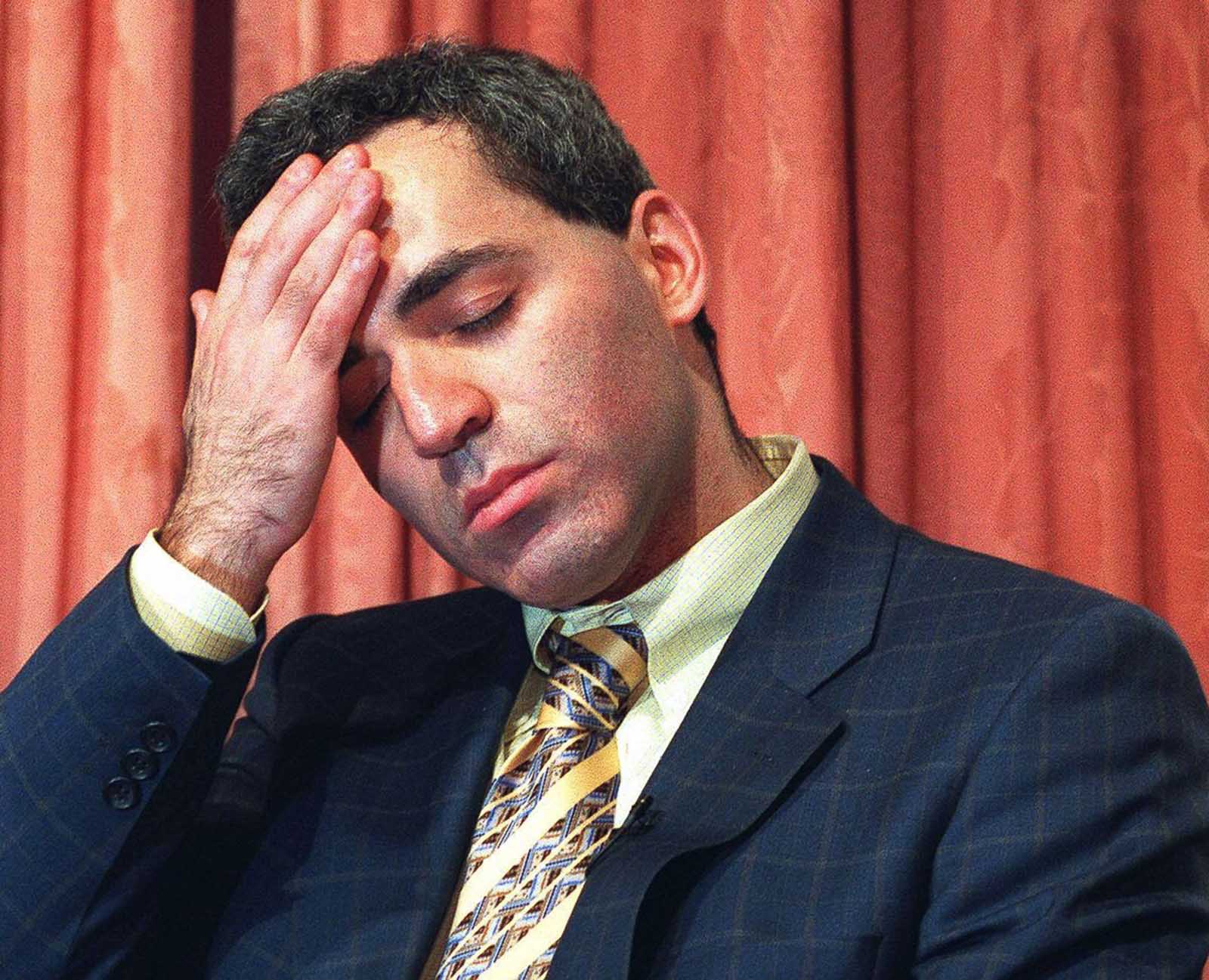

Kasparov holds his head in his hands as IBM scientist Joseph Hoane makes a move for Deep Blue at the start of the final game. May 11, 1997.

Kasparov wears a look of dejection after being swiftly defeated by Deep Blue in their final game. May 11, 1997.

Kasparov reflects on his loss to Deep Blue in their final game. May 11, 1997.