In the year 1927, a new chapter was written in the history of human flight. In a time when aviation was still a fledgling endeavor, Charles Lindbergh dared to imagine and achieve what had long eluded even the most intrepid pilots.

In the year 1927, a new chapter was written in the history of human flight. In a time when aviation was still a fledgling endeavor, Charles Lindbergh dared to imagine and achieve what had long eluded even the most intrepid pilots.

Setting off from Roosevelt Field in New York, his world’s first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean to Paris was not merely a journey of physical distance, but a testament to the relentless pursuit of human progress.

This audacious endeavor, undertaken against the backdrop of a society captivated by the promise of flight, thrust Lindbergh into the global spotlight and elevated him into the pantheon of aviation legends.

Crowd assembled at Roosevelt Field to witness Lindbergh’s departure.

The flight was inspired by Raymond Orteig, a New York hotel owner, who offered a challenge that would ultimately spark one of the most iconic achievements in aviation history—the solo, nonstop transatlantic flight.

Raymond Orteig’s prize was simple but audacious: a reward of $25,000 (equivalent to around $400,000 today) for the first aviator to successfully complete a solo flight between New York and Paris.

The offer was initially made in 1919, a time when aviation was still in its infancy and crossing the Atlantic seemed a near-impossible feat.

The Orteig Prize remained unclaimed for years, with several aviators considering the challenge but ultimately facing the immense difficulties of the task.

However, in the late 1920s, a young and determined pilot named Charles Lindbergh emerged as a contender.

Crafted by Ryan Airlines, the Spirit of St. Louis was more than just a machine; it was a masterpiece of engineering designed to overcome the challenges of endurance and distance.

Crafted by Ryan Airlines, the Spirit of St. Louis was more than just a machine; it was a masterpiece of engineering designed to overcome the challenges of endurance and distance.

With its distinctive monoplane design, the aircraft showcased a streamlined aesthetic that minimized drag and maximized fuel efficiency.

Its wings were fitted with custom fuel tanks that allowed Lindbergh to carry the necessary fuel for the arduous journey.

At the heart of this feat of engineering was the Wright Whirlwind J-5C radial engine. While not the most powerful engine available at the time, it was chosen for its reliability and fuel efficiency, critical for a flight that spanned over 3,600 miles of open ocean.

Lindbergh’s cockpit, positioned ahead of the wings, afforded him optimal visibility—a feature that would prove indispensable during his solo flight.

The engine was rated for a maximum operating time of 9,000 hours (more than one year if operated continuously) and had a special mechanism that could keep it clean for the entire New York-to-Paris flight.

The engine was rated for a maximum operating time of 9,000 hours (more than one year if operated continuously) and had a special mechanism that could keep it clean for the entire New York-to-Paris flight.

It was also, for its day, very fuel-efficient, enabling longer flights carrying less fuel weight for given distances.

Another key feature of the Whirlwind radial engine was that it was rated to self-lubricate the engine’s valves for 40 hours continuously.

Lubricating, or “greasing,” the moving external engine parts was a necessity most aeronautical engines of the day required, to be done manually by the pilot or ground crew prior to every flight and would have been otherwise required somehow to be done during the long flight. The fuselage was made of treated fabric over a metal tube frame, while the wings were made of fabric over a wood frame.

The fuselage was made of treated fabric over a metal tube frame, while the wings were made of fabric over a wood frame.

The plywood material that was used to build most of Lindbergh’s plane was made at the Haskelite Manufacturing Corporation in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

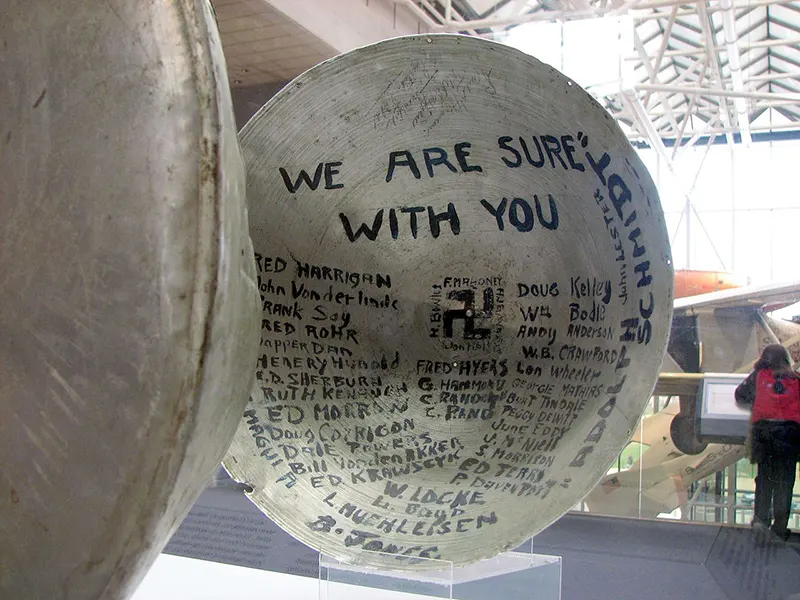

A small, left-facing Indian-style swastika was painted on the inside of the original propeller spinner of the Spirit of St. Louis along with the names of all the Ryan Aircraft employees who designed and built it.

It was meant as a message of good luck prior to Lindbergh’s solo Atlantic crossing as the symbol was often used as a popular good luck charm with early aviators and others.

The Spirit mobbed by a crowd at Croydon Air Field in South London on May 29, 1927.

In the early morning of Friday, May 20, 1927, Lindbergh took off from Roosevelt Field on Long Island. His destination, Le Bourget Aerodrome, was about seven miles outside Paris and 3,610 miles from his starting point.

He was “too busy the night before to lie down for more than a couple of hours,” and “had been unable [to] sleep.

“It rained the morning of his takeoff, but as the plane “was wheeled into position on the runway,” the rain ceased and light began to break through the “low-hanging clouds.”

A crowd variously described as “nearly a thousand” or “several thousand” assembled to see Lindbergh off, and he “walked around the plane on a final tour of inspection” after stepping from a “closed car where he had waited.”

For its transatlantic flight, the Spirit was loaded with 450 U.S. gallons (1,700 liters) of fuel that was filtered repeatedly to avoid fuel line blockage.

Charles Lindbergh became the first man to fly the Atlantic solo on May 21, 1927.

With the relentless hum of the engine as his only companion, he navigated through the unpredictable skies, facing challenges ranging from fatigue to the constant specter of mechanical failure.

The 33 and a half hours Lindbergh spent in the air were a testament to human endurance and innovation.

The cockpit of the Spirit of St. Louis held more than just instruments and controls; it held the dreams and aspirations of a generation.

The navigation was manual, the conditions were precarious, and the risks were immense.

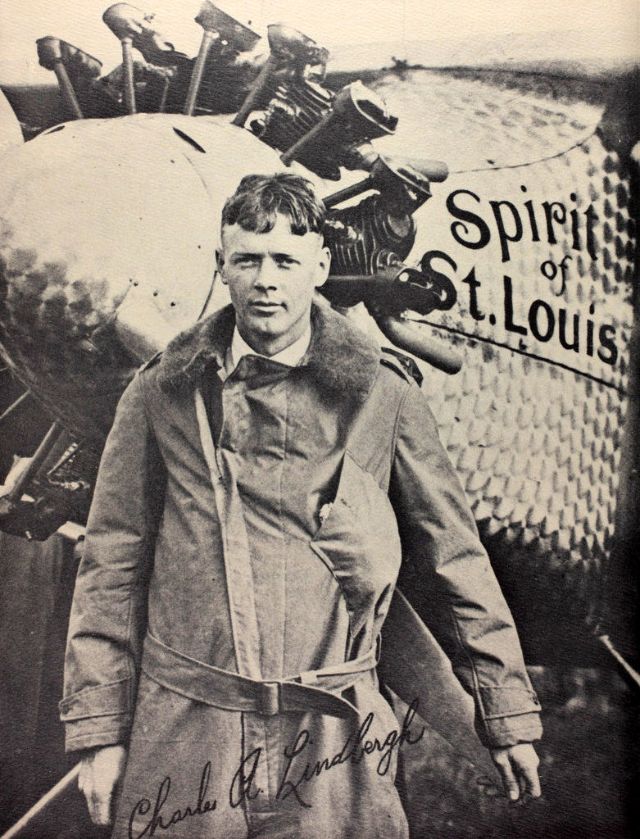

Lindbergh poses with Spirit behind, circa 1927.

Lindbergh’s biggest challenge during his transatlantic flight was simply staying awake. Between his pre-flight preparations and the 33.5-hour journey itself, he went some 55 hours without sleep.

Lindbergh went so far as to buzz the surface of the ocean in the hope that the chilly sea spray would help keep him awake, but 24 hours into the journey, he became delirious from lack of rest.

He later wrote of mirage-like “fog islands” forming in the sea below, and of seeing “vaguely outlined forms, transparent, moving, riding weightless with me in the plane.”

Lindbergh even claimed the apparitions spoke to him and offered words of wisdom for his journey.

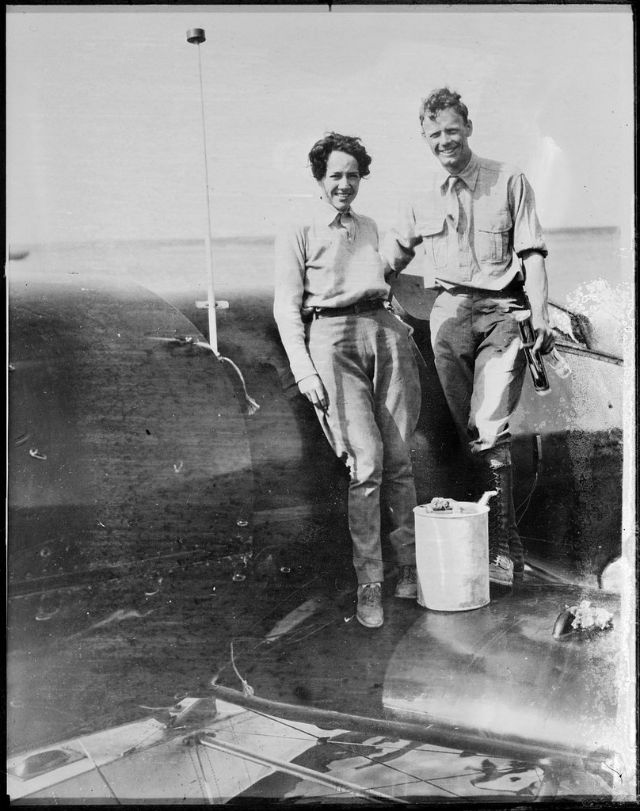

Pulling the propeller on the Spirit.

Eventually, the English coast appeared ahead of him, and he was “now wide awake.” A report came from Plymouth, on the English coast, that Lindbergh’s plane had started across the English Channel.

News soon spread across both “Europe and the United States that Lindbergh had been spotted over England,” and a crowd started to form at Le Bourget Aerodrome as he neared Paris.

At sunset, he flew over Cherbourg, on the French coast 200 miles from Paris; it was around 2:52 PM New York time.

Charles Lindbergh with his famed Spirit of St. Louis plane, circa 1927.

Over the 33 hours of his flight, Lindberg faced many challenges, which included skimming over storm clouds at 10,000 ft (3,000 m) and wave tops at as low as 10 ft (3.0 m).

The aircraft fought icing, flew blind through fog for several hours, and Lindbergh navigated only by dead reckoning (he was not proficient at navigating by the sun and stars and he rejected radio navigation gear as heavy and unreliable).

He was fortunate that the winds over the Atlantic canceled each other out, giving him zero wind drift—and thus accurate navigation during the long flight over the featureless ocean.

Lindbergh and four workmen in front of Spirit.

On arriving at Paris, Lindbergh “circled the Eiffel Tower” before flying to the airfield. He flew over the crowd at Le Bourget Aerodrome at 10:16 and landed at 10:22 PM on Saturday, May 21, on the far side of the field and “nearly half a mile from the crowd,” as reported by The New York Times.

The airfield was not marked on his map and Lindbergh knew only that it was some seven miles northeast of the city.

He initially mistook it for some large industrial complex because of the bright lights spreading out in all directions—in fact the headlights of tens of thousands of spectators’ cars caught in “the largest traffic jam in Paris history” in their attempt to be present for Lindbergh’s landing.

A crowd estimated at 150,000 stormed the field, dragged Lindbergh out of the cockpit, and carried him around above their heads for “nearly half an hour.”

Lindbergh with Spirit.

Lindbergh received unprecedented acclaim after his historic flight. In the words of biographer A. Scott Berg, people were “behaving as though Lindbergh had walked on water, not flown over it”.

The New York Times printed an above the fold, page-wide headline: “Lindbergh Does It!” and his mother’s house in Detroit was surrounded by a crowd reported at nearly a thousand.

He became “an international celebrity, with invitations pouring in for him to visit European countries,” and he “received marriage proposals, invitations to visit cities across the nation, and thousands of gifts, letters, and endorsement requests.”

After landing, Lindbergh was eager to embark on a tour of Europe. As he noted in a speech a few weeks afterward, his flight marked the first time he “had ever been abroad,” and he “landed with the expectancy, and the hope, of being able to see Europe.”

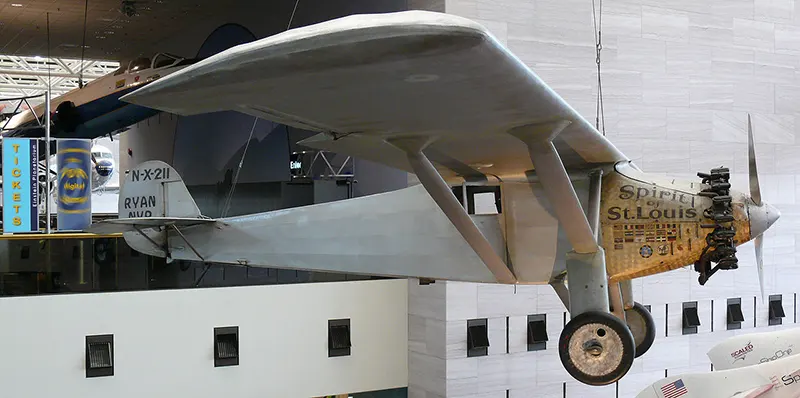

The Spirit at the National Air and Space Museum.

In winning the Orteig Prize, Lindbergh stirred the public’s imagination. He wrote: “I was astonished at the effect my successful landing in France had on the nations of the world.

It was like a match lighting a bonfire.” Lindbergh subsequently flew the Spirit of St. Louis to Belgium and England before President Calvin Coolidge sent the light cruiser Memphis to bring them back to the United States.

Arriving on June 11, Lindbergh and the Spirit were escorted up the Potomac River to Washington, D.C., by a fleet of warships, multiple flights of military pursuit aircraft, bombers, and the rigid airship Los Angeles, where President Coolidge presented the 25-year-old U.S. Army Reserve aviator with the Distinguished Flying Cross.

“Spirit of St. Louis” cockpit, Washington, D.C.

The Spirit of St. Louis appears today much as it appeared on its accession into the Smithsonian collection in 1928, except that the gold color of the aircraft’s aluminum nose panels is an artifact of well-intended early conservation efforts.

Not long after the museum took possession of the Spirit, conservators applied a clear layer of varnish or shellac to the forward panels in an attempt to preserve the flags and other artwork painted on the engine cowling.

This protective coating has yellowed with age, resulting in the golden hue seen today.

Inside of the original propeller spinner of the Spirit of St. Louis.

Smithsonian officials at some point planned to remove the varnish and restore the nose panels to their original silver appearance when the aircraft was to be taken down for conservation, but later decided that the golden hue on the engine cowling will remain, as it is part of the aircraft’s natural state after acquisition and during its years on display.

The effort to preserve artifacts is not to alter them but to maintain them as much as possible in the state in which the Smithsonian acquired them.

Nose of the Spirit of St. Louis, with the Wright Whirlwind Radial engine visible.

The legacy of Charles Lindbergh’s world’s first solo, nonstop transatlantic flight extends far beyond the boundaries of that moment in 1927.

It stands as a reminder that dreams, when coupled with determination and innovation, have the power to transform the ordinary into the extraordinary.

Lindbergh’s journey inspired generations of aviators, engineers, and adventurers, shaping the very fabric of aviation progress.

The Spirit of St. Louis on display in the National Air and Space Museum.

Charles Lindbergh with guests.

Lindbergh and Dwight Morrow, Atlantic City, NJ, May 5, 1930.

Lindbergh, in one of the many parades in his honor, in Hartford, Connecticut.

Governor Fuller pins medal on Lindberg at the State House.

Lindbergh, Gov. Fuller and Mayor Nichols.

Charles Lindbergh in the open cockpit of airplane at Lambert Field, St. Louis, Missouri in 1923.

Charles Lindbergh and father, Charles. A. Lindbergh. 1909.

Aviator Charles Lindbergh and his mother in 1930.

Charles Lindbergh and Anne Spencer Morrow were married on May 27, 1929.

Portrait of young Charles Lindbergh.

Charles Lindbergh, 1927.

Charles Lindbergh, circa 1927.

Charles Lindbergh in a Boeing F3B-1, BuNo A-7739, VB-2B, USS Saratoga, February 1929.

Lindy and Mrs. Lindy, June 1929.

Lindy and wife at Churchill, Manitoba, Lake Baker – sixth leg of vacation flight from Washington, D.C. to Tokyo, 1931.